Two people central to Radical Acts are Jane Marriott, the Director of Harewood House Trust, and Hugo Macdonald, the exhibition curator.

We sat down for a chat with Jane and Hugo, to look back on the evolution of Radical Acts and find out what visitors can expect.

Thank you both for finding the time to chat, especially in these busy two weeks before Radical Acts opens! Where did the idea for the Biennial come from?

Jane Marriott: Harewood House Trust is a charity and a museum, and it’s been set up as such since 1986. Our purpose is to conserve the House, the gardens and the wonderful collections. But more than that, we want to create exhibitions that excite our visitors, introducing them to new things, new artists, new ideas.

And so back in 2018 we decided that we wanted to do an exhibition about craft. It’s really interesting how many people have become interested in craft, in thinking about materials and in showing their support of local makers and artists. And of course, Harewood House, built in the late 1700s, has the most incredible craftsmanship from Chippendale furniture, to Robert Adam interiors. to John Carr architecture. So we thought Harewood is the perfect place to continue that great tradition of craftsmanship. When we started talking about the exhibition, we got brilliant feedback from people in the field, saying that makers and crafts in this country need that platform.

How did Hugo become involved?

Jane: What was really refreshing in the first conversation I had with Hugo was that, because his background is in writing, he puts craft within the context of how we live today. From that first conversation, I knew that he wasn’t just a wonderful curator, just picking beautiful objects; we’d be working with someone who would really take a step back and challenge us to think about craft in a different way. And so that’s when we invited Hugo to do the first Biennial, Useful/Beautiful, which was shown in 2019.

Hugo, can you tell us what you thought of Harewood when you first arrived and what inspires you about Harewood?

Hugo Macdonald: On my first visit I was overwhelmed, just like a lot of people probably are when they first come to a property of such magnificence. Every time I visit, I feel like I learn something new. There are so many layers not just to what you see, but also what you discover about people who have lived and worked in the House. The craftsmanship has been added to over decades and generations, centuries even. That’s where I find the challenge in curating the Biennial צ how do you introduce a contemporary layer that makes sense for what exists there already, but also brings something of today into the mix? How can we help people understand Harewood’s historic stories, but also put them in the context of contemporary life? How do we keep Harewood feeling alive?

How did you decide what to do for the second Biennial?

Jane: It’s not a case of saying, here’s what we want, Hugo, can you please do that? It’s a series of conversations. For the first Biennial, we invited multiple makers to respond to the House; we agreed that the format worked, but that this time we wanted to focus on a smaller number of really special makers. We also decided to exhibit pieces outdoors as well as indoors.

Our discussions began pre-Covid, thinking about the environmental crisis and what the role of these great estates can be in helping with that; to give this platform to great makers to talk about how craft can make a difference with sustainability, regenerative design, those sorts of topics. And then, of course, Covid came along and whilst we didn’t shift from those themes, we created a more nuanced response, which Hugo is very well placed to talk about more.

Hugo: The world was changing quite quickly, and our Biennial was an opportunity to address other connected subject matters that were coming to the surface. For example, how we think about well-being on a personal but also social and environmental level; and Black Lives Matter. The murder of George Floyd was a catalyst for many more conversations about racial and social injustice and given Harewood’s origins, we really wanted to include that as part of our exhibition. A lot of these subjects are things that craft deals with in a very open way, and craft can help ask important questions.

With that in mind, we decided to highlight people and projects who are engaged with asking questions about climate change and about society: how we relate to ourselves, the environment, each other. We called it Radical Acts because the word radical comes from the Latin word radix, which means roots; and each of the projects in the Biennial explores how things from the past can be a way of understanding the present. We have some very big names in the world of craft and we have some graduate students; it’s important to us that we are a platform that celebrates people at the top of their game, but also emerging interesting voices too.

Jane, what has surprised you about how Radical Acts has come together?

Jane: Probably how the makers bring such a wide variety of stories – very personal stories.

For example. we spent several hours speaking to Fernando Laposse, who talks about this incredible cooperative that he’s worked with in a village in Mexico, which is where he was born. He works with women who use the waste material from growing heritage corn to make these incredible luxury objects which are sold all around the world. His passion for the story and the women and this incredible cooperative really struck a nerve with me.

Then there’s Eunhye Ko, who is working with us as a younger maker coming into her career, with objects such as hair dryers and everyday electrical items. And you think, well, how on earth is that going to fit into a Biennial? Why will anyone be interested in that? But she works with them in in a very personal, creative way to challenge perceptions of things that we would throw away or replace much more quickly, like hairdryers or hoovers or everyday electrical items.

So I think the surprise for me is the variety, how personal those stories are and how we can relate to them. And I think people will really, really enjoy these 16 different stories from makers and feel a lot of empathy with them.

Hugo, how do you want people to feel when they visit Radical Acts?

Hugo: It has always been very important to us that we create a positive exhibition, an optimistic exhibition that feels entertaining and interesting, and that makes people feel like we can all do small things that join together to make a big difference to help address some of these challenges that we face in life. It is, like Jane says, a surprising exhibition, but we’re not telling people what to do. We are inviting people to come and see how these crafts-people are working in different ways to think about possible futures. And each of the exhibitors has a simple message behind their work that we hope will connect with visitors to Harewood, that visitors will take these ideas back home and think about how they relate to their own lives.

So, for example, Good Foundations International says water is precious. We mustn’t take it for granted. Good Foundations International go into communities who don’t have fresh water and help them to discover local sources, then build skills and businesses in the community to make ceramic water filters, which is an ancient technology for cleaning dirty water. Good Foundations International see firsthand what the impact is on people’s lives when they don’t have access to fresh water, and they alert privileged people to the fact that it’s a resource that should not be taken for granted. That’s one example of a simple message that we hope will connect with people because most of us switch on a tap without even thinking about it.

Hopefully people will reflect on the exhibition for a long time afterwards, and it might influence the small choices we make every day.

Hugo: Absolutely. I feel like exhibitions should be starting points rather than something that begins and ends. I want to open people’s eyes and minds to think about things slightly differently, or to understand how things connect; and to always feel included in that discussion. Never to feel like they are being lectured at or told. We really want to use the Biennial as a way of inviting people into Harewood and making them feel as welcome as possible. And like I said before, to introduce stories into this environment that are surprising, but also very relevant.

What would you say to each visitor as they view the exhibition?

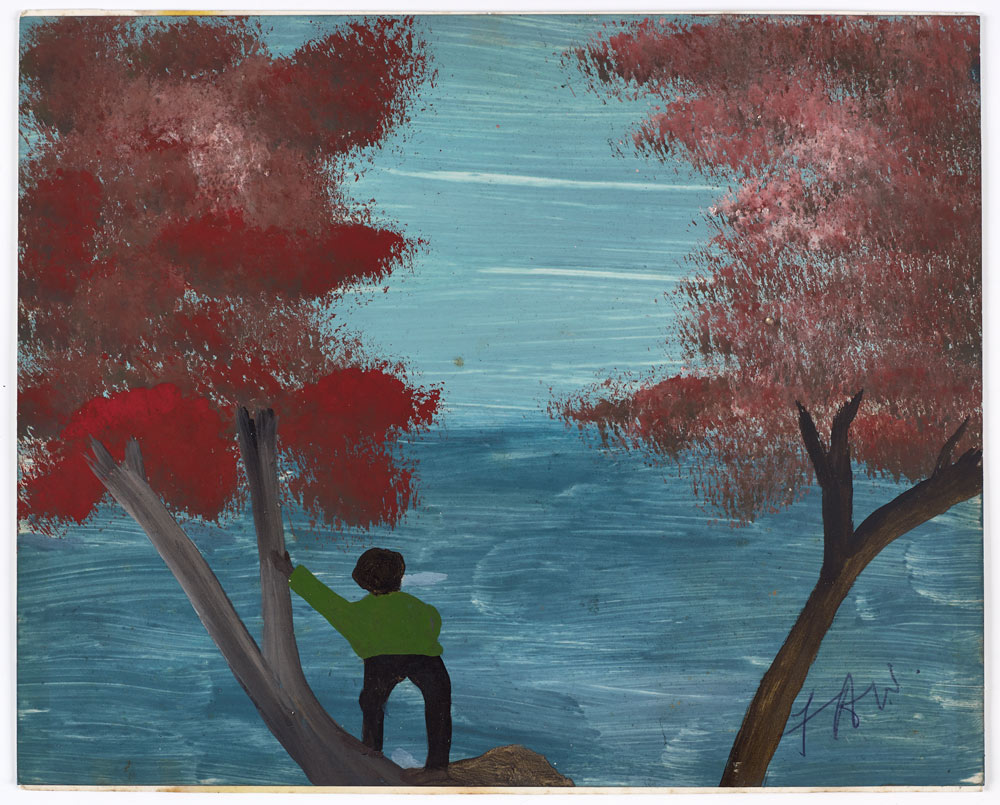

Jane: I encourage you to experience the exhibition as a set of very personal stories, that will talk about that person or that studio’s approach to craft and what’s important to them. What you will hear is those makers saying it in their own voice. I suspect it will surprise a lot of people. I hope some of the choices seem quite bold and some will be quite poignant and quite thoughtful, like Mac Collins and his very personal response to the house and his own history and heritage. But there are also moments of just sheer joy and beautiful objects that are a window into it that particular maker and their achievements.

If I saw the visitor afterwards, I’d remind them that we’ve also got several podcasts and films with the makers – so you can return to those craftspeople who really stuck in your mind and inspired you to do something.

Hugo: One of my favourite things in the exhibition is actually not an exhibit. We have built a blank wall in the Servants’ Hall where we ask the question, What is your radical act? We hope this will encourage visitors to think about what they do in their day to day lives, and that could be something as simple as having a reusable shopping bag or reducing car journeys. That’s what I hope people will be thinking about as they move around the exhibition.

One thing people might be inspired to do is get hands-on with craft-making, and for that they can look forward to our Make it Harewood weekend in July. There will be workshops, music and food, all to show that everybody can be involved in craft and everybody can benefit in some way. It’s a wonderful recurring theme throughout the show, that working with your hands makes you feel happy. It improves your well-being mentally, physically, psychologically and Make it Harewood is a wonderful opportunity for people to have a go. So visit the website for more details on when that will be and who will be involved.

Thank you both!