Whilst exploring Harewood’s Old Kitchen, visitors may notice an unusual decoration perched above one of its cooking ranges – a large shell belonging to a green sea turtle. In this article, Harewood’s volunteer researcher, Olivia Wyatt, and Curator, Beckie Burton, discuss the turtle shell’s wider significance and a recent discovery in the archive.

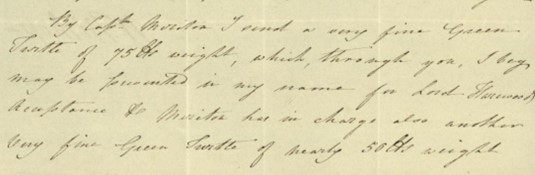

An intriguing letter, written by William Bishop to John Wood Nelson in the summer of 1800, was recently discovered in the Lascelles family’s West Indian archive held at the Borthwick Institute in York. It reads:

“I send a very fine Green Turtle of 75 lbs weight, which, through you, I beg may be forwarded in my name for Lord Harewood’s acceptance and […] another very fine Green Turtle of nearly 50 lbs weight which I must request you will do me the kind favour of placing on your own table.”

The letter raises many questions. Who was William Bishop? Why did he send several sea turtles halfway across the world from Barbados to Britain? And why might the recipients want to ‘place them on their table’? The answers reveal the historic cultural and social significance of the Caribbean green sea turtle, as well as help us understand the ways in which the Lascelles family managed their West Indian plantations.

Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) are native to tropical and subtropical waters around the world, including the Caribbean region. During the eighteenth century turtles were an important source of food for island inhabitants, providing the native, free and enslaved populations with meat, eggs and oil. Turtle meat was also used to ‘revive’ famished Africans arriving on slaving ships. European colonists learned about the nutritional benefits of the green sea turtle from the indigenous Miskitu people of eastern Nicaragua and Honduras, and many Europeans initially believed turtles possessed magical medicinal qualities.

The culinary reputation of the sea turtle inevitably spread via colonial trade networks to Europe, with live turtles shipped across the Atlantic in large tubs of seawater to ensure their ‘freshness’ upon arrival. Dishes such as turtle soup were created, which involved boiling and baking turtle meat with varying combinations of vegetables and spices; the bestselling eighteenth-century cookery book The Art of Cookery by Hannah Glasse contained several turtle recipes, such as how to prepare it ‘the West India Way’. Turtles were rare commodities in Europe, and as such its meat came to be considered a delicacy. Turtle dishes developed a reputation as high-status cuisine, available only to those with access to global trade and its closed systems of communication, transport and finance. Accordingly, serving a dish containing turtle at the dinner table implied a level of status and wealth, and became a way for hosts to show off and impress guests.

The turtle shell hanging in the Old Kitchen at Harewood today almost certainly belonged to a turtle that was consumed in the House or possibly at an external event hosted by the family; Edwin Lascelles, the builder of Harewood House, is recorded as having provided a ‘Turtle-feast’ to the ‘gentlemen of [his] neighbourhood’ in ‘Chapel-Town’ in 1767. In fact, the presence of several turtle shells in Harewood’s wider collection reveals an eager consumption of this high-status commodity by the Lascelles family. The shells themselves were kept for decorative purposes, a culinary trophy that continued to hold prestige and intrigue even after the turtle itself was gone.

The gift of a green turtle, then, was one of cultural capital, offering prestige and status to its new eighteenth-century owners. It is also representative of the broader context of exploration, conquest and enslavement that defined British colonialism. William Bishop’s turtles would have been shipped alongside other desirable Caribbean products such as sugar and rum, their production enabled by the systematic trade and exploitation of enslaved African Caribbean people. This was a trade that the Lascelles family dominated, and were amongst its most successful beneficiaries.

But who were the individuals involved in this particular transaction of turtles and what was their relationship?

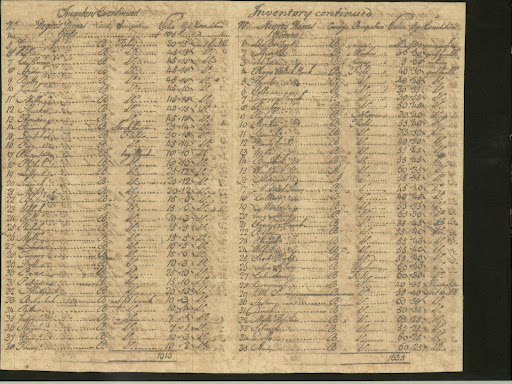

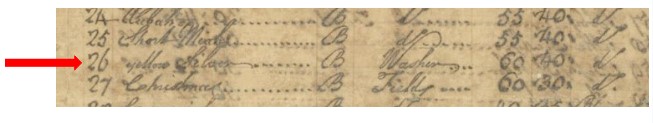

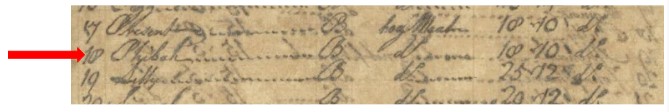

By 1800, the Lascelles family managed a network of 24 Caribbean plantations located across several Caribbean islands: Barbados; Jamaica; Trinidad; and Grenada. However, their business interests were administered from Britain, relying on a hierarchy of managers to carry out day-to-day operations on both sides of the Atlantic. Both William Bishop and John Wood Nelson (the second recipient of a turtle after ‘Lord Harewood’, later 1st Earl of Harewood) were a part of this system.

Nelson was a senior partner in the Laselles family’s London commission house, a business established to sell products (such as sugar) produced and shipped over from Lascelles family plantations. Bishop was Nelson’s counterpart in Barbados, appointed to oversee the running of Lascelles family’s estates on the island. Men based in the Caribbean such as Bishop were known as ‘attorneys’ and were responsible for reporting back to the commission house; it took approximately two months for letters to arrive by ship from the Caribbean to London, so it was essential for the Lascelles family to hire powerful and trustworthy individuals to deal with immediate problems on plantations, such as uprisings. In the mid-1790s, William Bishop was selected as an attorney because he had been born in Barbados and belonged to a prominent family with pre-existing connections to the Lascelles family; he had also already served as interim governor of Barbados from 1793-94. By 1800 – the date of the gift of turtles – Bishop had risen to the position of President of the Barbados Council.

Bishop’s letter is dated 18 July, but the red stamp on the envelope, dated 26 September, indicates that it was received by Nelson over two months later. (Photograph by Olivia Wyatt)

This hierarchical management structure explains why Bishop wrote a letter to Nelson to request that his gift of a turtle was “forwarded in [his] name for Lord Harewood’s acceptance”. As Lord Harewood’s main contact, Bishop needed Nelson to present the turtle, though he was keen to ensure he received due credit as the sender. Interestingly, Bishop was also obliged to send Nelson himself a turtle, understanding the importance of impressing both Lord Harewood and a senior partner within a bureaucratic management system. In fact, the dismissal of Bishop’s predecessor, John Prettyjohn, for incompetence may have increased his desire to make a good impression. Nevertheless, the not-so-subtle size difference between the two turtle gifts – Lord Harewood’s being 25 lbs larger – demonstrates Bishop’s acknowledgement of the difference in status and authority between the two recipients.

In this context, then, the gift of a green turtle can also be seen as a calculated act of flattery and professional point-scoring. It is unknown whether Lord Harewood or Nelson acknowledged their extravagant gifts, though it is certain they were gladly received.

Olivia Wyatt and Beckie Burton