Harewood House Trust has marked the tercentenary of Thomas Chippendale with the acquisition of a copy of his famous catalogue of furniture designs, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director. Read the latest instalment of the Chippendale300 journey from Professor Ann Sumner, Historic Collections Advisor.

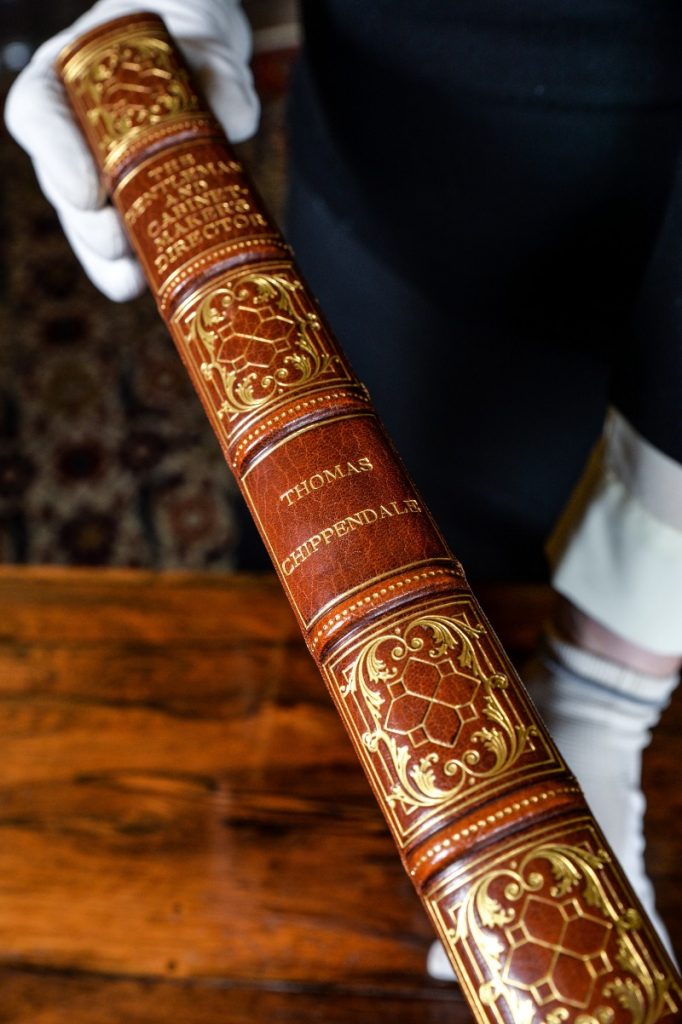

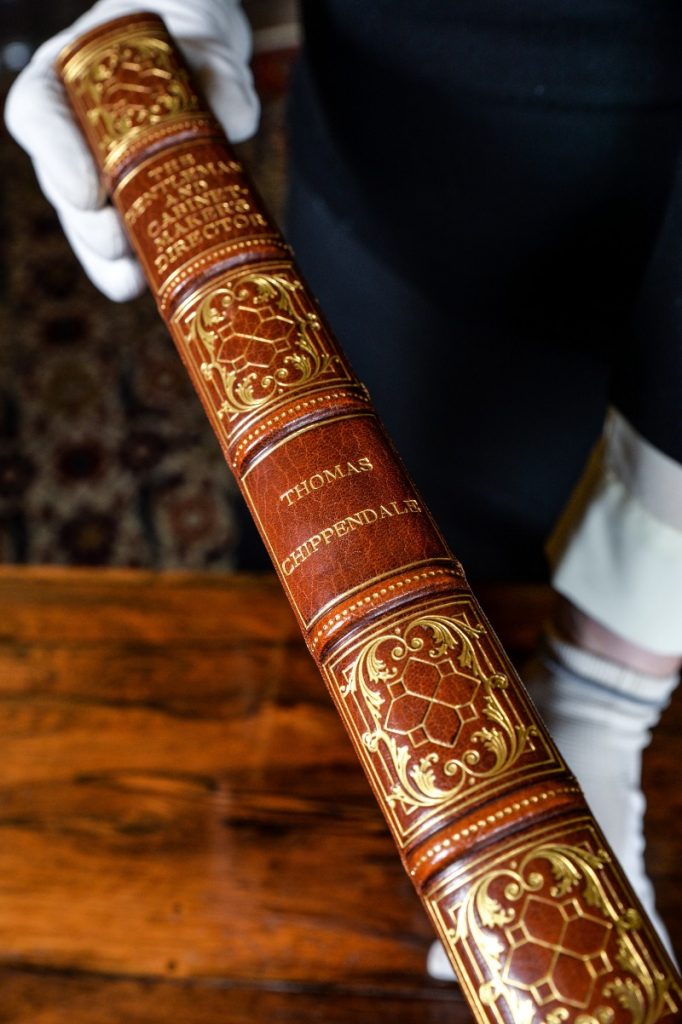

This copy is a 2nd edition dated 1755 and was owned by the 1st Earl of Harewood. In excellent condition it was acquired from a New York dealer by Simon Phillips at Ronald Phillips Ltd, who generously donated the volume back to the Harewood House Trust permanent collection.

The fine, engraved armorial bookplate is of Edward Lascelles, 1st Earl of Harewood (1740 – 1820), cousin of Edwin Lascelles who commissioned the Chippendale firm at Harewood and who succeeded him. It has a fine 19th century, brown morocco and gilt binding, by Riviere and Sons of Bath, with a spine in seven compartments and the crest of the Earl of Harewood, decorated with fine gilt tools, with gilt edges. It is in overall excellent condition.

The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director by Thomas Chippendale, 2nd edition 1755, with 19th century brown Morocco leather and gilt binding, Harewood House Trust.

Chippendale produced the first edition of The Gentleman and Cabinetmaker’s Director in 1754 as a commercial enterprise to improve his professional reputation and attract new business. He could not have envisaged its wider success, the impact it would have on 18th century furniture styles and his own legacy. It is the very reason that so many people today still know the name ‘Thomas Chippendale’ while some of his talented rival cabinetmakers are not as renowned today. Chippendale explained the title in the preface, ‘as being calculated to assist the one in the choice, and the other in the execution of the designs, which are so contrived that if no one drawing should singly answer the Gentleman’s taste, there will yet be found a variety of hints sufficient to construct a new one’. The planning of the publication throughout 1753, was no doubt organised to coincide with his significant move in 1754 to St Martin’s Lane and to a new workshop, with the formation of a relationship with financing partner the Scot, James Rannie of Leith, so his firm would be ready and prepared for any new custom it generated. He worked closely with the talented engraver Matthias Darly who produced the illustrations from Chippendale’s drawings, many of these original designs for the Director survive in the MMA New York and in the V&A.

While some furniture designs had occasionally been published before 1754, Thomas Chippendale’s Director was the first ambitious publication on such a large scale. It included designs for ‘Household Furniture’ in the ‘Gothic’, ‘Chinese’ and ‘Modern Taste’, the latter referring to what would today be termed the French Rococo style. The Director was initially launched in April 1754, with 308 supporters signing up, many of these were tradesmen with some architects and sculptors as well as potential patrons from the nobility and gentry. The majority of those who subscribed however, were craftsmen engaged in the furniture trade.

It was a relatively expensive publication compared to the slim volumes of furniture designs gathered together previously. Subscribers pre-publication, would have paid £1 14 s 0d for bound copies or, after publication £2 2s 0d. Chippendale recognised the advantages commercially of gaining orders from booksellers and attracted four London dealers as subscribers too but the only regional bookseller was Stabler and Barstow of York. The quick publication of a second edition the following year, which was basically a reprint of the original with corrections indicates the popular success of the Director. It was clearly a central tool in generating new commissions for his firm and it is a copy of the 2nd edition which Harewood House Trust has recently acquired. Undoubtedly the publishing of the Director was a success. All major known commissions by the Chippendale firm date from after its publication. The first two volumes contained 161 engraved plates showing a rich range of fashionable household furniture. The first two editions were dedicated to the Earl of Northumberland, a distinguished patron of the arts. Many aristocrats ordered copies of the Director but the majority of subscribers were practicing tradesmen.

Ribband Back Chairs, an engraving from Chippendale’s Director, 1755 Harewood House Trust.

The finest example of a commission closely related to the Director designs is at Dumfries House in Ayreshire, Scotland, which is where I went recently to lecture and to see the magnificently preserved early furniture. The fact that a copy of the 2nd edition was in the Lascelles family possession suggests that this book potentially belonged to Edwin Lascelles and was inherited by his cousin the 1st Earl of Harewood and that it influenced Edwin’s decision making a decade later when he decided to employ Thomas Chippendale at Harewood, although we cannot prove this book actually belonged to him. The only fully documented Chippendale furniture dating from the period when the Director was published and illustrating his fully Roccoco period is that at Dumfries House, making it a unique survival of the Chippendale firm’s activities in the 1750s.

By contrast, Edwin Lascelles at Harewood was not commissioning Chippendale until the late 1760s. Thomas Chippendale first came to Harewood in 1767 and his first furniture arrived here in 1769, so over 15 years after the first publication of Director. Harewood therefore is an example of his later mature Neo-Classical furniture, rather than his early Rococo style. Nevertheless there are still illustrated plates in the book which closely relate to furniture at Harewood today. The acquisition of this copy of the Director, returning it to Harewood in Chippendale’s tercentenary year, was extremely important to us in piecing together the influences there may have been on Edwin Lascelles when he made the decision to employ Chippendale for the firm’s most lavish and expensive commission, which would late over 30 years and be completed by Thomas Chippendale Junior.

The publication of the Director also inspired other workshops to emulate this success and create their own furniture pattern books. Chippendale responded to a weekly publication by William Ince and John Mayhew with the publication of his own 3rd revised edition of the Director in 1762 and rose to £3 for a bound copy. The third edition was a significant expansion, reflecting the changing taste of the period with a significant shift towards Neo-Classicism and Chippendale’s response to what other rivals were doing too. It contained 200 engraved illustrations and was dedicated to HRH Prince William Henry. Ten original plates were discarded and 50 new engravings were included. This third edition was published five years before Chippendale set foot in Edwin Lascelle’s new house at Harewood, reflecting how established the workshop was by the time he was commissioned to furnish the Adam interiors at Harewood.

We might have assumed that the Lascelles family would have owned a third edition of the Director, but this was not the case, it was an earlier second edition that passed down in the family. The three editions of the Director have played a significant part in Thomas Chippendale’s legacy not only in Britain but it ensured his international reputation, influencing design in France, Spain, Scandinavia and crucially in America. We are not alone in celebrating the acquisition of a copy of the Director – the Chippendale Society announced in January 2018 that they had acquired a copy of the Director in French, a very rare edition which was actually owned by a German Friedrich Otto von Munchhausen (d 1797) who was the model for the fictional Baron Munchausen. This Director has its original leather binding Germany was one of the most receptive markets for the book, as well as France and we even know that Catherine the Great of Russia owned a copy.

Visiting Dumfries House last month in the middle of the heatwave, I was shown around by head guide John Morrison who pointed out a wealth of Chippendale’s fine mahogany furniture, extravagant Rococo mirrors and a unique moment in the Earl of Dumfries’ study where the fine mahogany library table, with rich ormolu handles, supplied in 1759 is on view. Resting on the desk is a copy of Chippendale’s Director, the later edition of 1762 open on a plate illustrating a very similar desk. That copy of the Director is on loan to Dumfries House from another famous Yorkshireman Alan Titchmarch. The Earl had visited London in early 1759 and Chippendale’s workshop in St Martin’s Lane. It proved to be an expensive shopping expedition as he was so taken by Chippendale’s designs. By May 1759, 39 crates of furniture arrived safely in Scotland, despite Chippendale’s concerns about damage en route from London.

At Harewood today there is one particular pair of commodes which relates to the Director designs. For decades now we have referred to two fine mahagony commodes as the ‘Goldsborough Commodes’ and one of the pair was lent to the excellent exhibition in Leeds Thomas Chippendale 1718 – 1779: A Celebration of British Craftsmanship and Design which closed in June this year. They probably date from earlier in Chippendale’s career than the main Harewood commission, perhaps stylistically to c 1765 We’ve always thought that they were supplied by Chippendale to Daniel Lascelles of Goldsborough Hall, the bachelor brother of Edwin Lascelles, who commissioned him at Harewood. Chippendale’s men worked at Goldsborough on various dates between 1771 and 1776 and there is a considerable group of furniture, later transferred to Harewood and elsewhere, which can be securely shown to have been designed for Goldsborough, notably from the dining room. However, Adam Bowett who was co-curator of the Leeds exhibition has clearly demonstrated that these two rococo commodes are not mentioned in the 1801 inventory of Goldsborough, nor in the Princess Royal’s list of furniture transferred from there to Harewood in 1930. He therefore, proposes that they were made for Harewood all along and were among the numerous mahogany chests of drawers recorded in the 1795 inventory. Could it be that they were early purchases which encouraged Edwin Lascelles to return to Chippendale when he required major pieces for his newly built Harewood House?

One of a pair of commodes (c. 1765-70) at Harewood House, previously thought to have been made for Daniel Lascelles at Goldsborough Hall.

The commodes are typically Rococo in style and demonstrate Chippendale’s typical design elements with their serpentine profile and the double ogee at the front and side aprons. Again there are scrolled foliate cartouches at each corner, carved volute feet, S-shaped keyholes and distinctively designed brass handles.Both are now united and displayed in the same room in Lord Harewood’s Sitting Room on the State Floor. Chippendale illustrated six ‘French Commode Tables’ (that is the ‘Modern’ or what we would call Roccoco style today) in the 1754 and 55 editions of the Director and altogether ten in the expanded 1762 edition. It was clearly a genre and style endured with his patrons and where he felt comfortable but Adam Bowett points out in the luxurious new catalogue for the exhibition that this commode ‘has hints of a nascent neo-Classicism seen in the oval paterae at the sides of the angle brackets in addition to the use of acanthus leaves, beading and husk flowers’ and he draws attention to the top drawer which ‘opens to reveal a baize-lined sliding shelf, bordered in mahogany, either for brushing clothes or for writing’. Recently taking students form the Attingham Summer School around Harewood we were able to open these draws and illustrate this to their gasps of amazement.

French Commode Table, a preparatory drawing for Chippendale’s Director and published in the 1754 and 1755 editions. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Today we open the Director on a page which illustrates one of Chippendale’s designs for ‘French Commode Tables’ which is very similar indeed to our ‘Goldsborough’ commodes, for while they may no longer be felt to have been made for Goldsborough and have in fact most likely been here at Harewood over the centuries, old habits die hard and we shall have now to remind ourselves that they are better described as the Harewood Rococo commodes!

Ann Sumner, Historic Collections Advisor for Harewood House Trust, and guide John Morrisson at Dumfries House

I thoroughly enjoyed my visit to Dumfries and the opportunity to see a Collection which relates so closely to the designs in the Director and on 1 August, Yorkshire Day, I lectured here at Harewood for our members celebrating the legacy of one of Yorkshire’s most famous sons. We hope to welcome you to Harewood to see our new Director on display this summer and our exhibition Designer, Maker, Decorator which runs until 2 September 2018.

Maria Mahon, Kitchen Gardener, Harewood House

Maria Mahon, Kitchen Gardener, Harewood House