How to keep in touch when you can’t physically see each other? In this world of hyperconnectivity, are people picking up their pens again and writing letters?

How to keep in touch when you can’t physically see each other? In this world of hyperconnectivity, are people picking up their pens again and writing letters?

Rebecca Burton, curator and archivist, looks at a more romantic method of communication: handwritten letters.

Preparing for the new exhibition in the House, Becoming the Yorkshire Princess, I have been incredibly fortunate to work with a series of heartwarming letters written by HRH Princess Mary and some of her closest family members.

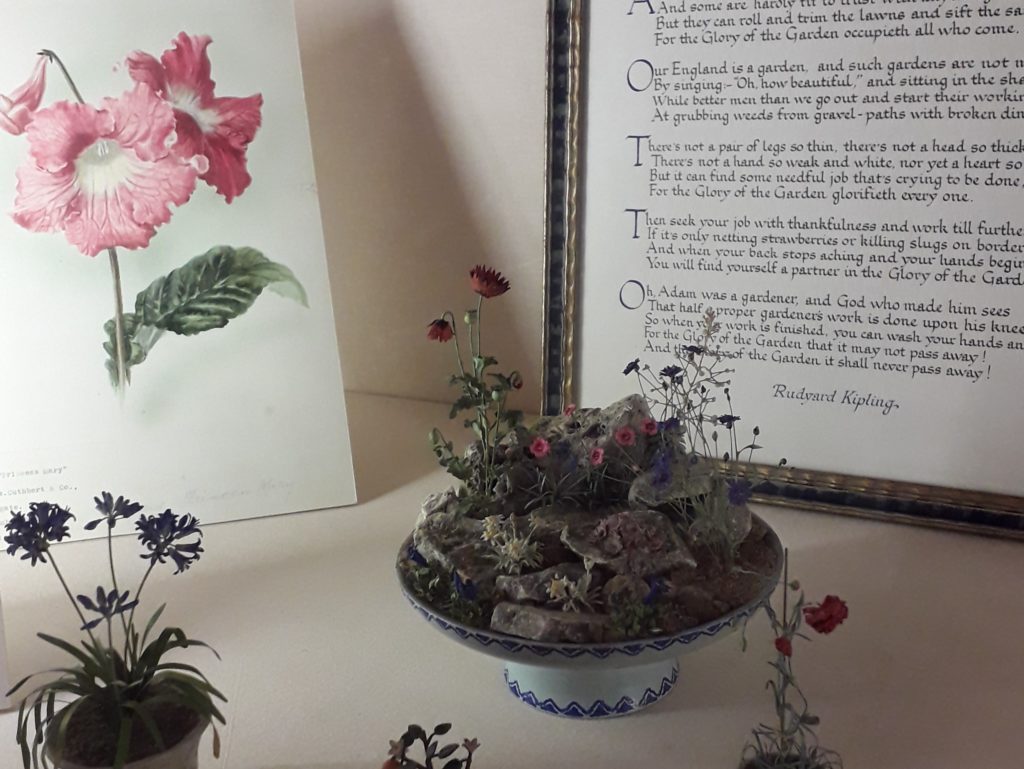

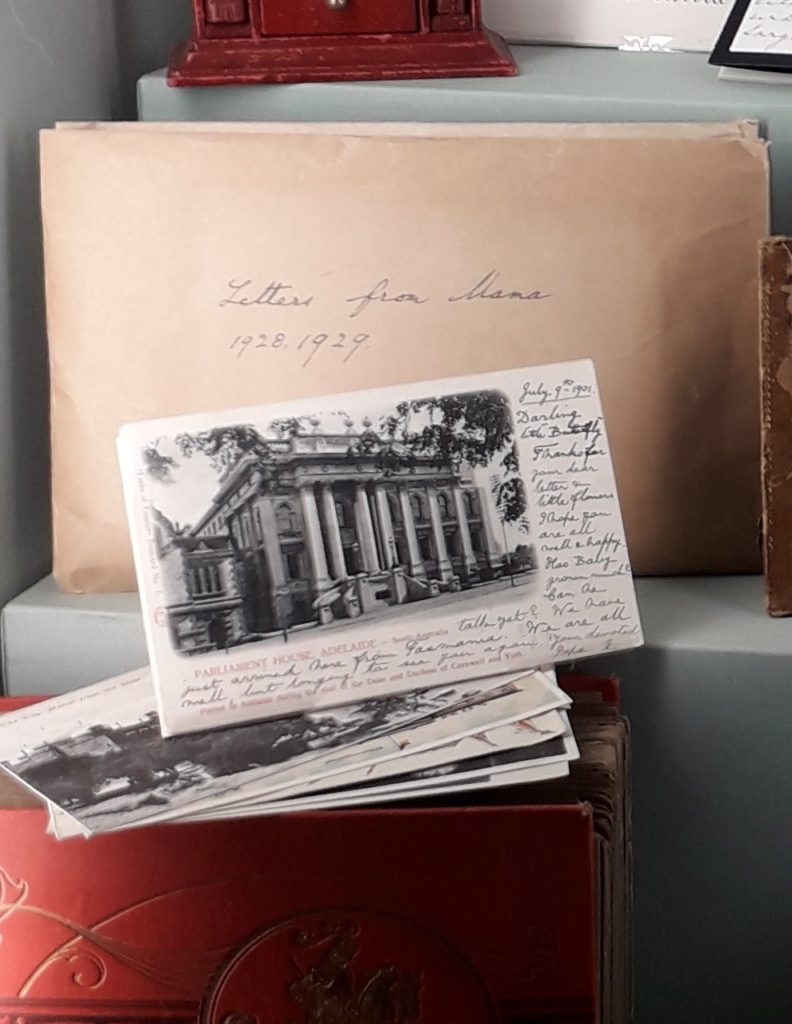

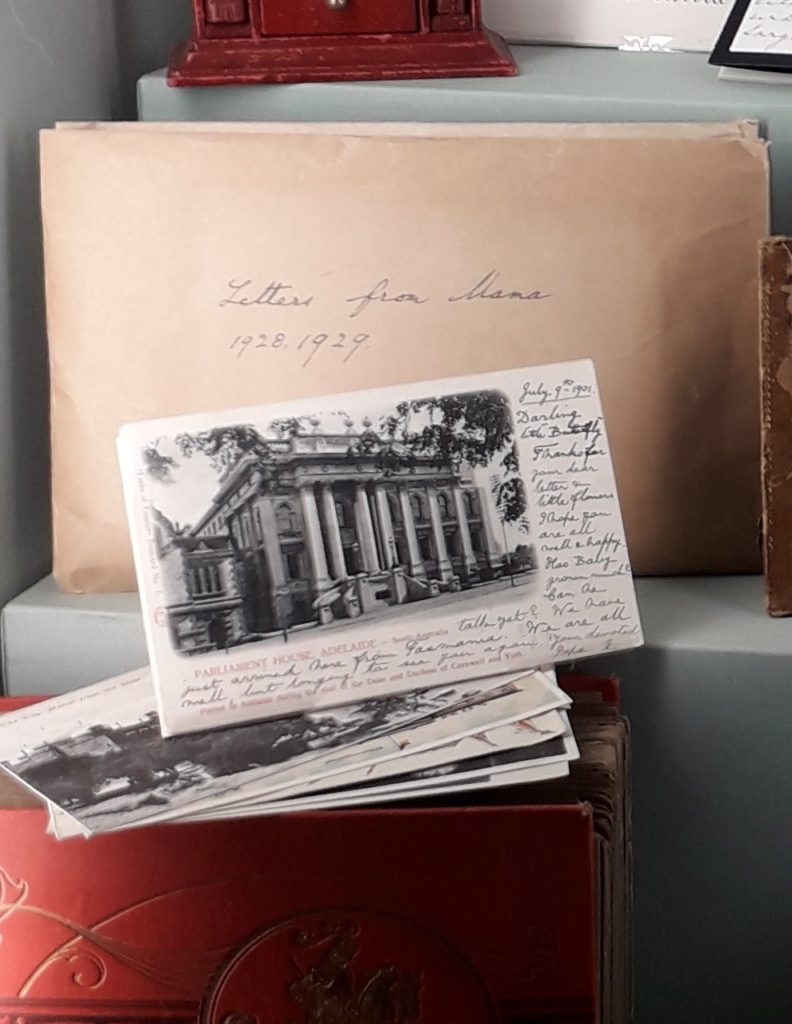

Princess Victoria Alexandra Alice Mary of York (1897-1965) was the only daughter of the Duke and Duchess of York, later King George V and Queen Mary. During Mary’s childhood, her parents were often away from home touring what was then the British Empire, in their roles as the Prince and Princess of Wales. They wrote frequently to one another, often enclosing personal mementos with their letters, such as photographs, pressed flowers and postcards (which Mary collected and compiled in large albums, encouraged by her father).

“Many thanks for your dear letter and the nice piece of white heather which I shall keep…..I hope you have put all the postcards I sent you in your book, I thought they were very pretty.”

Prince of Wales (later King George V) to Princess Mary, 1903

Mary’s childhood letters – written in both English and French, give us a window into the daily routine of a royal child (which included lessons, riding and plenty of outdoor activities) and illustrate a rich picture of family life at Sandringham. Whilst Queen Mary’s distinctive joined-up handwriting can at times be hard to decipher, her letters to her daughter offer a personal, vivid and often amusing account of her and her husband’s travels abroad.

“Here we are in Cairo which is a most interesting place with many different things to see….Today we saw the Colossus of Ramesses II, a huge statue which unluckily has been broken and now lies on its back – we also saw some wonderful tombs. Only think, I actually rode a camel and rather liked it.”

Letter from the Princess of Wales (later Queen Mary) to Princess Mary, 1906

Mary’s father’s notes tend to respond more directly to Mary’s own correspondence, reflecting on her hobbies as well as encouraging academic progress. His writing is often succinct but his language personable and cheerful in tone, inscribed in a script that is more cautious and much less conspicuous than his wife’s.

“I was delighted to get your letter this morning…Your French is beautiful and your writing much improved. I am also pleased to hear that Mademoiselle is quite satisfied with you and that you are getting on well with your lessons…I am sure you could easily beat me at golf now as you have been playing so much lately.”

Letter from the Prince of Wales (later King George V) to Princess Mary, 1905

Throughout all the correspondance, there is a real sense of warmth and affection on both sides and we get access to emotion that is rarely observed in Royal sources (or any other kind of object for that matter).

“I hope you are quite well dear Mama, we shall be so pleased when you come home, we are going to hang our flags out of the house windows the day you come home. I send you and Papa a bear hug and a fat kiss.”

Princess Mary to the Duchess of York (later Queen Mary), 1901

Despite this family’s extraordinary position within society, it would be hard to tell that this correspondence was written by a princess and a future king and queen; their words such that could be written by any daughter, mother or father, and their themes universal.

“Thank you very much for the postcards you sent me. I have got a lot now…Georgie sends you and Papa a kiss, we are all quite well, with lots of love and kisses, from Mary.”

Princess Mary to the Princess of Wales (later Queen Mary), 1906

What Mary’s letters offer also is a contrasting perspective to traditional historical narratives. Mary’s father in particular, who has often been described as a strict and undemonstrative parent, is shown in quite a different light.

Irrespective of their authors, handwritten letters are physical remnants of personal relationships and human connections. And as such they are undoubtedly some of the most rewarding historical material that I am lucky enough to work with. Despite the fact that Mary’s letters, both sent and received, were often unceremoniously and incongruously stashed away in old, used envelopes by their recipients, for me they are amongst some of Harewood’s most precious objects. I am reminded often, through a private joke or a doodle in the margin, of their intensely personal nature and the responsibility that comes with caring for and studying them.

Becoming the Yorkshire Princess a new exhibition about Princess Mary, will remain in the House this year and available to view as soon as Harewood is able to open. Read more about the exhibition here.