Barbados

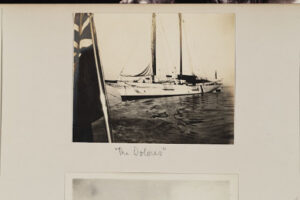

In 1906, the Lascelles family set sail in their yacht, the Dolores, for a several month-long holiday to the Caribbean. Accompanied by domestic staff and a crew of 14 men, the family visited at least six West Indian islands on their island-hopping tour: Barbados; Trinidad; Grenada; Martinique; Dominica and Jamaica.

The Dolores

The Dolores Crew

Unusually, the trip is known to us only through photographs – those taken by Florence, the 5th Countess of Harewood – who was a keen amateur photographer, and who compiled and annotated her photographs in albums. The photographs that document the family’s West Indian trip show that they often visited popular tourist destinations, though the family also visited several of their estates in Barbados.

Two centuries earlier, Edwin Lascelles, builder of Harewood House, had been born on the island of Barbados. This country became the epicentre of the Lascelles family’s business interests in the West Indian sugar trade, a trade that thrived on the systematic and brutal exploitation of trafficked Africans. At its peak, Edwin owned or managed a total of 24 West Indian sugar plantations, which included over 3000 enslaved individuals. These individuals were considered chattels (property that was not land), having been stripped of their rights and identities, and forced to work under brutal conditions.

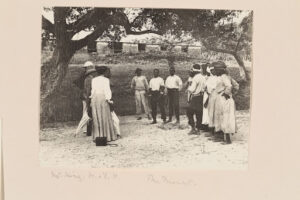

Following the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, many of the Lascelles family’s remaining estates were sold off, though by 1906, the Lascelles family still had possession of four plantations in Barbados – Fortescue, Thicket, Mount and Belle. The 5th Countess took a small number of photographs of Mount and Belle, capturing some of the individuals who most likely lived and worked there during the 20th century. Further research is needed to understand more about the plantation’s workforce and management during this period.

The Mount Estate, Barbados (Owned by the Lascelles family from 1780 – 1974).

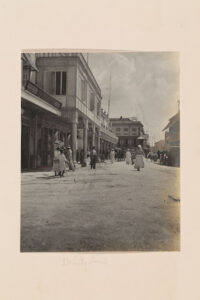

View of Bridgetown, Barbados

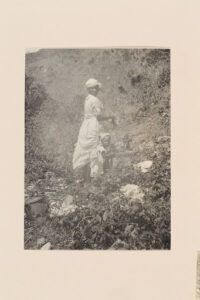

During their stay in Barbados, the family also visited its capital, Bridgetown, which had, during the 17th and 18th centuries, been a British trading port for sugar and enslaved Africans. Henry Lascelles – father of Edwin – had once been the town’s Collector of Customs, which had enabled him to invest in every aspect of the 18th century sugar and slave trades. The family also visited a number of nearby landmarks, such as Cole’s Cave. During the 19th and early 20th century, Cole’s Cave was (and remains to this day) a popular destination for tourists, known for its underground rivers and geological features. The cave was also known to have been a refuge for escaped enslaved individuals during the 18th century.

Photographs taken whilst on an excursion to Cole’s Cave, Barbados.

Photographs taken whilst on an excursion to Cole’s Cave, Barbados.

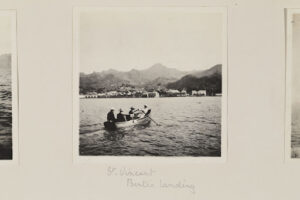

From Barbados, the family travelled south to Trinidad, then back north to the Windward Islands. During this part of the journey, the Dolores navigated past St Vincent – an island with a territory smaller than the size of Leeds. This was a deliberate route that enabled them to return George ‘Bertie’ Robinson – the Lascelles family’s footman, who had been brought to Harewood by the 5th Earl and Countess following one of their previous trips to the West Indies – to his country of birth. Bertie had accompanied the family on their trip, presumably fulfilling his role as footman until disembarking for St Vincent. One of the 5th Countess’ annotated photographs identifies Bertie (and a large trunk) being rowed to shore in a small boat. The intention was probably to drop Bertie off on St Vincent where he would remain, however archival records document that he made his way back to Harewood independently. Find out more about Bertie Robinson’s story here.

“Bertie landing, St Vincent”.

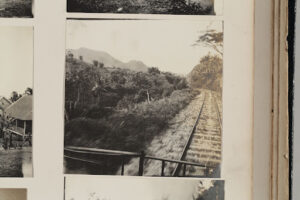

Finally, the family headed westwards to Jamaica. Jamaica was one of the leading sugar producers in the world during the 18th and early 19th centuries. It was also the location of 8 of the Lascelles family’s historic estates, which together had a total acreage of over 20,000. The 5th Countess’ photographs show that the family took a ride on the now abandoned rail line between the town of Bog Walk in the Parish of St Catherine and Port Antonio on the northeast coast of Jamaica. The rail line was built in the late 19th century to enable the easy transportation of goods, such as bananas and citrus fruits, for shipping. The rail line passed through the town of ‘Harewood’ (which had its own station – ‘Harewood Halt’) that took its name from the nearby Williamsfield plantation. Williamsfield had been one of the largest former Lascelles sugar plantations, which had been worked by almost 300 enslaved individuals. No doubt the Lascelles family stopped off during their sojourn along the line to visit the Jamaican town that had taken (or perhaps been given) their name – whether they understood the full and lasting impact of their family’s business interests on the island and its inhabitants beyond historic place names is unlikely.

Images taken from the Bog Walk to Port Antonio railway

Images taken from the Bog Walk to Port Antonio railway

The 5th Countess’ photographic record of the Lascelles family’s 1906 Caribbean tour offers a rare visual glimpse into the life and landscapes of the West Indies in the early 20th century, however it is one that is undeniably nuanced and idiosyncratic. Florence’s images are framed by her perspective as a wealthy White British tourist and landowner, one that was both aristocratic and female, and who also had a family history that was intertwined with that of the region and its people.