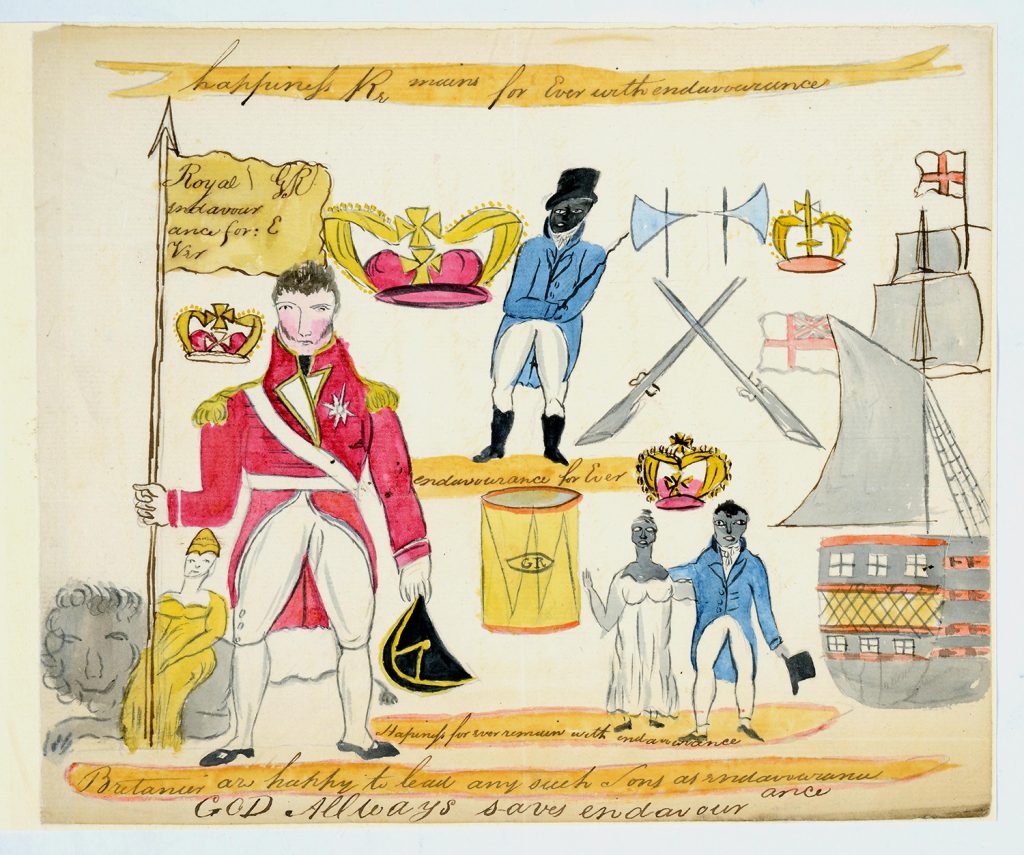

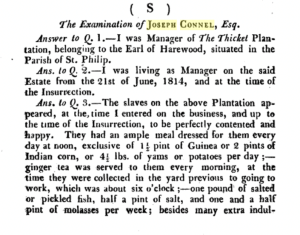

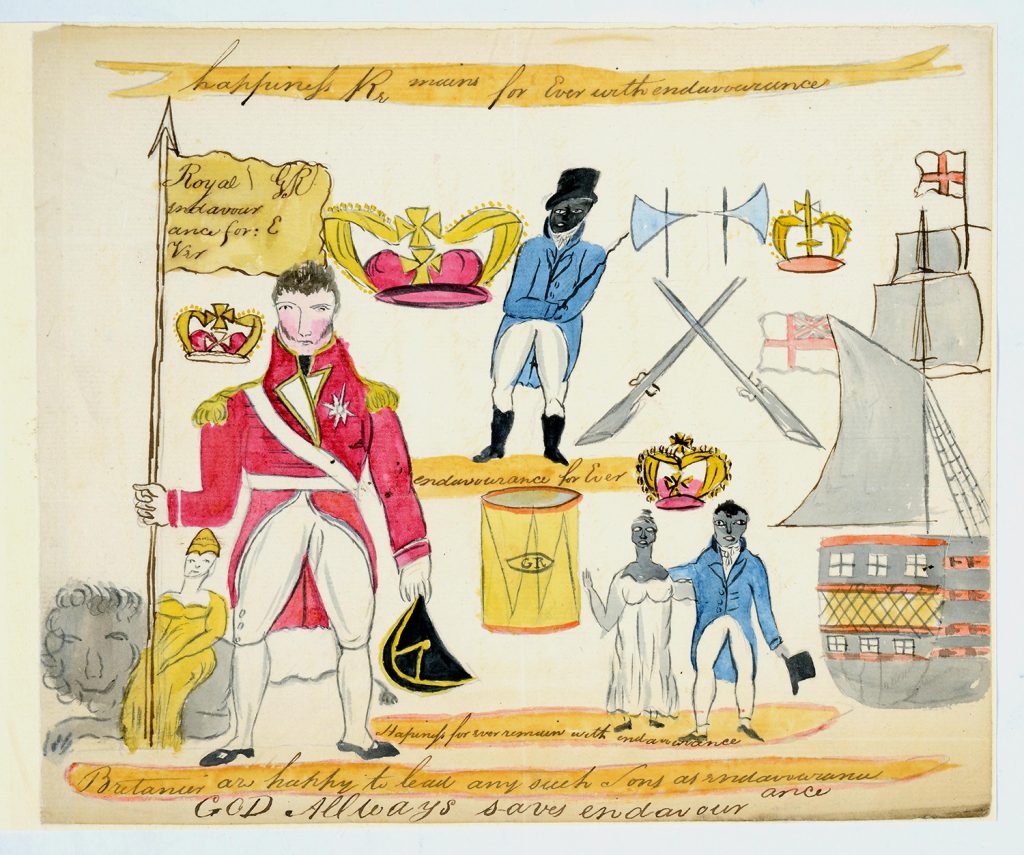

Sketch of a flag said to have been used by enslaved rebels during Bussa’s Revolt. It demands freedom but also expresses loyalty to the British Crown, 1816. National Archives MFQ 1/112 (2).

On the evening of the 14 April 1816 – 208 years ago to this day – fires were lit in the sugar cane fields of the Bayleys plantation in the parish of Saint Philip on the island of Barbados. These fires signaled the start of a coordinated uprising by the island’s enslaved population, becoming the largest such event in its history. Over the course of the next three days, battles were fought between the freedom-fighters and the British militia affecting over 70 plantations and spanning more than half the island.

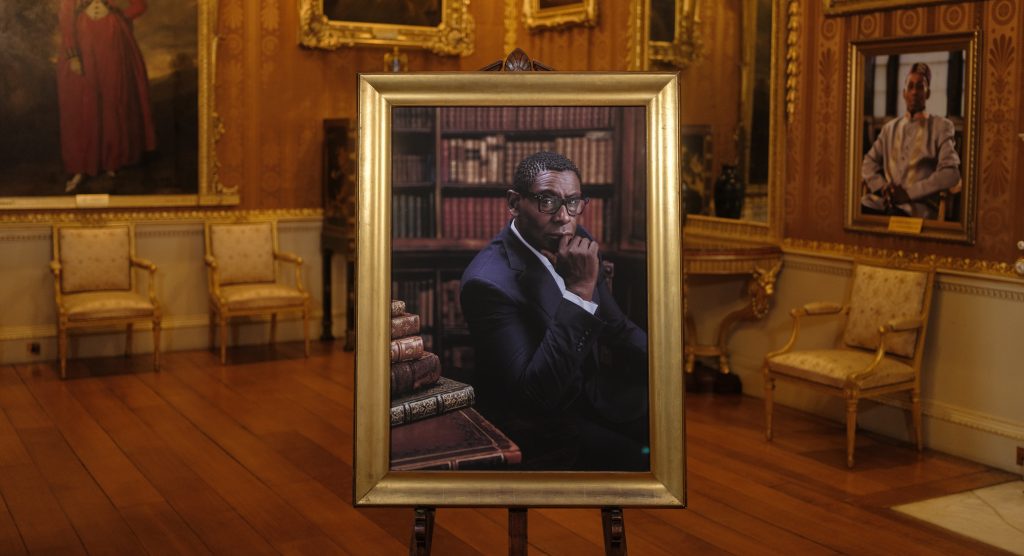

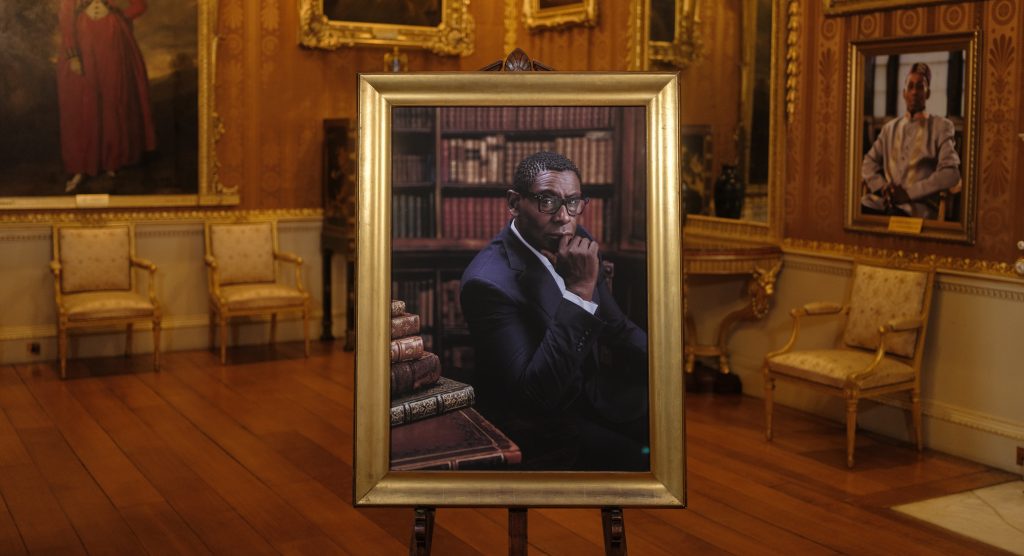

In her latest blog, Researcher Olivia Wyatt discusses Harewood’s links to this major event in Barbadian history, as well as its connection to the Black British actor David Harewood, the sitter of the newest portrait in our collection, now on permanent display in the Cinnamon Drawing Room.

In the decades that followed the abolition of the British trans-Atlantic slave trade in 1807, many enslaved Barbadians felt disappointment and frustration at the continued delay of emancipation. On Easter Sunday, 14 April 1816, they decided to take matters into their own hands. An African-born enslaved ranger named Bussa orchestrated a revolt that spanned across half of Barbados and commanded approximately four hundred rebels in battle. According to Colonel Codd, commander of the British troops garrisoned on the island, the rebels felt that “the island belonged to them and not to white men, whom they proposed to destroy.”

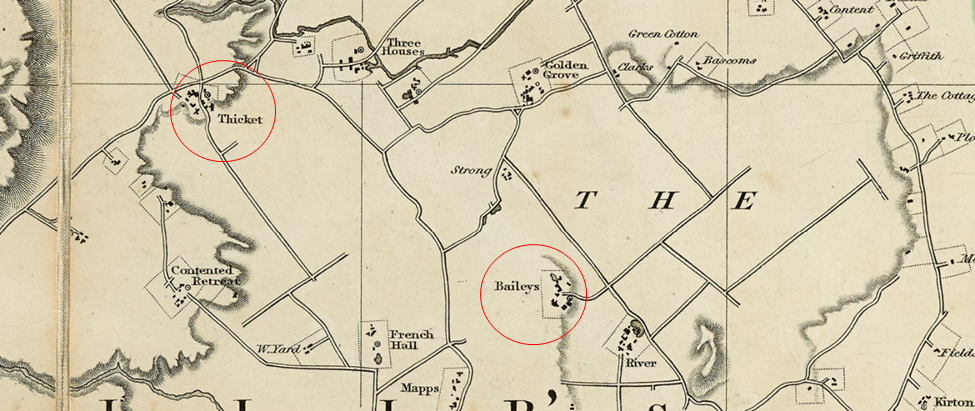

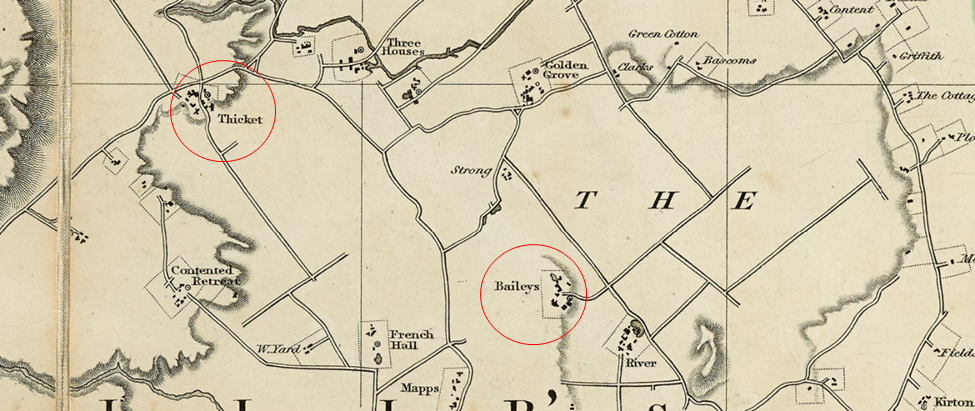

Survey of Barbados, 1827, showing the proximity of Thicket and Bayleys plantation in the parish of St Phillip. Image courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

One of the plantations that played an instrumental role in the uprising was the Thicket plantation owned by the Lascelles family and located only 2km North West of Bayleys plantation, where Bussa was based and the rebellion began. While the enslaved individuals based at Thicket were not the instigators of the revolt (as had been the case in the foiled conspiracy on one of the Lascelles family’s plantations in Tobago in 1805) leading Caribbean historian Hilary Beckles has described activity on the plantation as “the core of the rebellion.”

Thicket’s enslaved Barbadians posed such a threat that Colonel Codd diverted his men to “where a body of the rebels were said to have made a stand” on the estate. A witness later testified that prior to the rebellion, one of Bussa’s co-conspirators, Jackey, “sent to a free man in the Thicket (who could read and write), to let the negroes at The Thicket know, that they might give their assistance.” The rebels at the Thicket adhered to Jackey’s instructions and engaged in fierce battle. Like many of the other plantations involved in the revolt, Thicket sustained significant damage – the rebels destroying profitable sugar crops and key productive buildings such as boiling and distilling houses, and British troops destroying the living quarters of enslaved Barbadians. At Thicket, damage amounted to £3989, though another of the Lascelles family’s plantations that also participated in the uprising, the Mount, sustained some of the costliest damage on the island, at £5150.

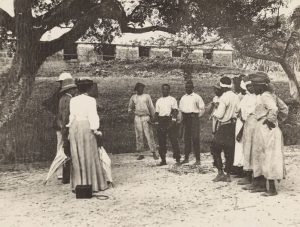

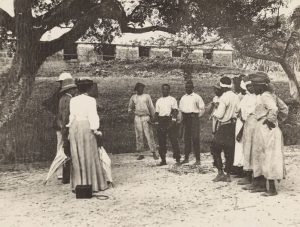

Photographs of the Mount plantation taken by Florence, 5th Countess of Harewood, 1906.

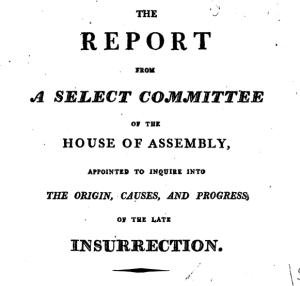

The rebellion was quashed by British troops after three days of fighting. Many died during battle, including Bussa himself, and even more rebels were executed or exiled as punishment. In the aftermath of the uprising, a committee was established to conduct investigations into the origins and causes of the rebellion. The committee included Richard Cobham, a resident enslaver and attorney to the Earl of Harewood who oversaw the management of his plantations in Barbados. Find out more about how the Lascelles family managed their plantations here

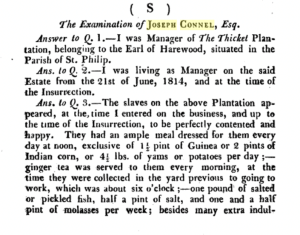

Joseph Connel, manager of the Thicket, was asked by the committee to shed light on the temperament of the enslaved before the uprising. He argued that they were “perfectly contented,” but “when correction was necessary (which was seldom), they were flogged with rods; and if crime was of any magnitude, they were confined in a solitary room, until they were made sensible of their error.” Nevertheless, several months following the rebellion, Cobham wrote to Harewood’s partner, John Wood Nelson, to express his belief that the rebels required a different type of punishment:

In answering your inquiry relative to the negroes Houses at the Mount, which were all totally burnt by the military, and nearly all at the Thicket Estate also, I must let you know that they are not yet restored, as it was the general opinion here that the negroes should not immediately enjoy their accustomed comforts, after their atrocious misdeeds against their owners: they have been, however, sheltered in the buildings they thought proper to spare. As soon as the boiling and distil houses at the Mount are completed I will have the negroes houses rebuilt. They remain tranquil. Seven of the prisoners belonging to his Lordship have been released and six remain to be tried.

By controlling their standards of living, Cobham sought to remind the African-Barbadians of the power of enslavers; that the island belonged to the White man, contrary to the (supposed) beliefs of the rebels. Cobham’s use of “remain tranquil” suggests that there was great anxiety about retaliation. However, not all enslaved Barbadians participated in the rebellion because they often feared repercussions, or sought the benefits of demonstrating loyalty to the upper classes. The Royal Gazette of Jamaica reported that four individuals, “among whom was one belonging to Lord Harewood”, were manumitted (freed) in January 1817, and received “the annual sum of Ten Pounds […] for their good conduct during the late rebellion.”

Bussa’s Rebellion failed to bring about emancipation, though it represented an important statement of resistance by enslaved Barbadians, demonstrating to British parliament their intent to demand freedom by force if it was not offered to them through reform. Nevertheless, it should be noted that despite these intentions, British parliament and local colonial governments attempted to minimise the implications of the rebellion, choosing to conclude that the enslaved had rebelled due to the ‘meddling’ of William Wilberforce and his (and his supporters’) apparent false promises of immediate emancipation. Bussa’s Rebellion was a shock to the British government and terrified it more than it was willing to admit, choosing to blame misinterpretation and manipulative tactics, rather than concede the widespread desire for freedom.

Missing Portrait No. 2, David Harewood by Ashley Karrell, 2023. Copyright Ashley Karrell.

The role of the enslaved individuals based at Thicket plantation during Bussa’s Rebellion is particularly significant in light of a new portrait that has recently entered the Harewood collection by the Leeds-based photographer Ashley Karrell. The sitter is the Black British actor and writer, David Harewood, whose great-great-great-grandparents, Richard and Betty Rose, were born enslaved on the Thicket plantation in 1817 and 1820. Richard and Betty Rose’s parents and possibly even grandparents were likely involved in the resistance.

Richard and Betty Rose were emancipated in 1833 and their son, Benjamin William, was born as a free man in 1840. While their ancestors may not have lived to witness the freedom they fought for, their victory manifests within the achievements of their descendants: those, like David Harewood, who commit their lives to tackling ongoing issues of racism, exclusion, and underrepresentation.

By Olivia Wyatt

Sources and further reading:

The Report from a Select Committee of the House of Assembly, appointed to inquire into the origins, causes and progress of the late insurrection. Published by T. Cadell & W. Davies, 1818.

Hillary McD. Beckles, ‘The Slave-Drivers’ War: Bussa and the 1816 Barbados Slave Rebellion’, Boletín de Estudios Latinoamericanos y Del Caribe, no. 39, 1985, pp. 85–110. JSTOR.

S. D. Smith, Slavery and Gentry Capitalism in the British Atlantic: The World of the Lascelles, 1648-1834. Cambridge University Press. 2006.